As I never made any separation between steps and story, I was amazed by those who were able to put them into different compartments, as if mind and body could somehow work apart from each other. Unless I had a reason to move, I was totally paralyzed." -Gelsey Kirkland, The Shape of Love

An alert mind is an actor's prerequisite. It must be exercised as continuously and with the same discipline as the body. Another major flaw of the untrained actor is to attempt to separate thoughts from actions. -Uta Hagen, A Challenge for the ActorA Challenge for the Actor has long been my desert island book. But I just came across Gelsey Kirkland's "sequel" to her penetrating and brutal first book, Dancing on My Grave. It's called The Shape of Love, and it records her "come-back" after drug addiction and eating disorders that dragged her from being a prima ballerina with New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre to the brink of death. I haven't read it in many years, but I remember underlining furiously as her quest for the truth always struck a deep chord in me as a performer.

In this "sequel" Kirkland tells the story of her return to the stage, this time with The Royal Ballet, with whom she felt the sort of camaraderie she could never find in New York. The Royal Ballet is evidently steeped in theatrical tradition, whereas, as English dancers apparently put it, "In America, they dance from the waist down."

As I read Ms. Kirkland's book, I wondered if she had ever read Uta Hagen's books on acting, or if Ms. Hagen had ever read of Kirkland's search as a ballet dancer for meaning for her movements on stage. The two are such kindred spirits that it's hard to imagine they don't know of each other much less that they are the best of friends. (Although, alas, Uta Hagen is no longer with us.)

The Shape of Love, like A Challenge for the Actor, is for performers who are determined to knock down any impediment to the truth. Why does a person do something when she does it? How is the way in which she does it completely determined by her circumstance (her previous location, with whom she was keeping company, what letter she just read, the weather, her need to get somewhere else, etc...) Previous moments shape all our destinations, like the thousands of points in a Seurat canvas, our movements are links in a chain but appear fluid because of the lightning speed of the brain and heart. When we stand back, we see one picture or story, but an actor must break apart each moment and see how it connects to the last and the next. The audience can watch a fluid story, but it is also watching beats, those precious moments in which a turn in the road is made. We make thousands of such turns every day. Just watch yourself make a cup of coffee. Where is the sugar bowl? Should I use the little spoon that's dirty on the counter or get a fresh one? Is that the phone ringing? It might be that date I had from last week finally calling! It might be the doctor with test results. Should I take it? Ignore it? What happened to that spoon? You see? Thousands of turning points.

Gelsey Kirkland arrived, miraculously, at this understanding of acting without having any formal training, other than mime work, which she did on the side in her years at ABT. In The Shape of Love she dives into the specifics with a tenacity and earnestness matched only by Uta Hagen's. A ballet, particularly a classical one, is a story with dialogue and destination just as is a stage play. But the dialogue is told in the hands, in the arms, in the particular placement of the feet and back that serve to embody the character's point of view, desires and relationships to her partners.

An actor will (and should) contemplate, consider, agonize if necessary, over why she is doing anything on stage. Art is not life, it is distilled life, so that it takes on a reality not more heightened, as is so frequently thought, but more clear. Extraneous movements happen from distraction throughout all of our days. An artist must pare those away and keep only what is essential to the story and the character. Then the moving painting, the fluid line, the story, the humanity rise to the surface and the mundane vanishes.

"I imagine that once you start thinking as an actress, it must be pretty difficult to accept working any other way." So says a young dancer Kirkland is coaching for the role of Giselle.

I began my years of performing as a ballet dancer. My first role, however, was mostly mime. I lucked into a group of visionary choreographers who sought to bring Antoine de St. Exupery's "The Little Prince" to life in ballet form. At ten years old, I was being asked to take one moment to think about a drawing given to me (the prince) by the aviator and the next moment to reject it. In that first moment I needed to see the painting, in the second moment I needed a reason for rejecting it, so that the act of rejecting it made sense in my body. A ballet is made up of thousands of moments. And nearly all of them, at least according to Gelsey Kirkland, and I am inclined to agree, must be thought through in this way.

And so when I began my life as an actor, at 12, I always felt that ballet was what gave me the key to acting. It was fascinating to read that Kirkland had this experience in reverse. You cannot get into an arabesque pique without rolling through the extending foot and passing through a paradoxically infinite number of points in space. So it felt with scene work in acting. Each moment depended on the last until a chain was formed, and rehearsals allowed for both the strengthening of the chain and its flexibility. (This may be one point where ballet and acting diverge dramatically: in acting, when we rehearse, we do so precisely to create the ability to be spontaneous, as paradoxical as that seems. In ballet, these finely tuned rehearsed moments might be more set in stone, as the body must move itself physically through space in the same pattern for every performance. Spontaneity in performance seems to run counter to the needs of ballet.)

Ballet of course has its technical feats. I don't know that the powerful fouettes of final acts are primarily motivated by story, but having been boosted by one's own conception of her place in the story, her reasons for every small gesture and delicate placement of her leg, a ballerina has given herself the wings to fly through the superhuman technical feats now required of dancers.

There is an infinite amount to say about both these fine artists and their books. If you are hungry for meaning in art, if you are fascinated by the techniques, if you simply love ballet or acting, find these books and read them.

|

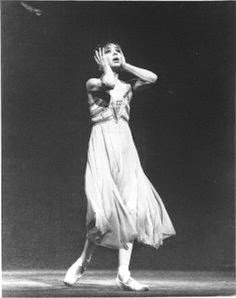

| As Giselle. |

|

| Life at a barre. |

|

| A complicated Juliet. |

|

| Once a dancer... |

Related: Tutu Much, Tutu Soon